All that good gamification stuff

In this writeup I summarise most prominent gamification principles based on gamification experts work and share some personal experiences.

Why gamification? TL;DR

Broadly speaking, any use of gaming tools in non-game context can count as gamification. And what are games? Games are fun, for most of the people anyways. They engage, bring us together, teach us, challenge us and reward. Most importantly, good games are also incredibly engaging. Even better news is all that good stuff is transferable to almost any experience.

Gamification has been there forever, some fields like education including adult education have embraced it long before it became e-education. Nowadays industries like social media, ed-tech, fitness (e.g. Strava), even health (e.g. Headspace) and banking (e.g. Cleo) all have at least some element of gamification.

Not every product can be structurally gamified but game bits can do wonders in most of the products in the following stages of the user journey:

Onboarding – could easily be one of the most fruitful stages for gamified experience. Onboarding typically implies a series of mundane steps and it’s that one touchpoint where almost every product can allow itself some freedom. An example: Arc’s browser onboarding has a visual wow effect with the whole screen buzzing in color and sound for a couple of seconds and it also gives new users a badge. A badge for nothing, if we think of it – for a sign up. However, it makes us feel like we are members of the new internet so to say, it triggers belonging and purpose.

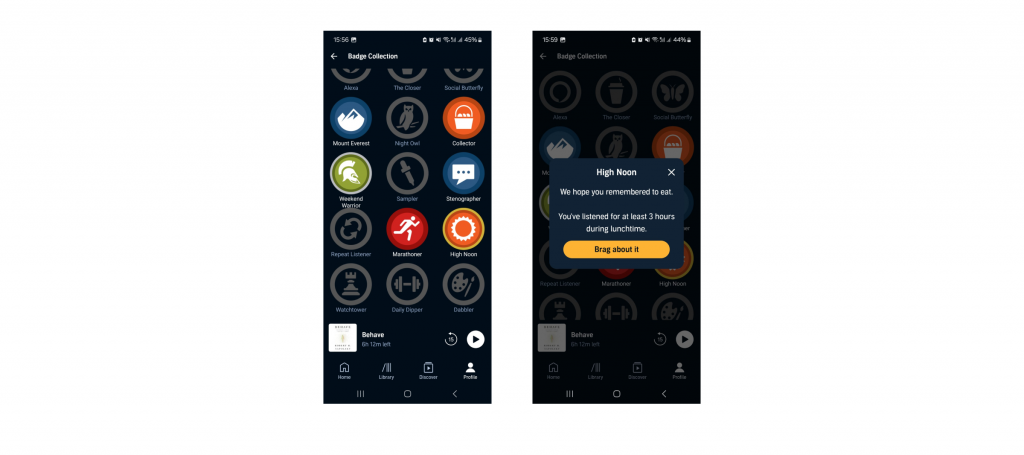

First few steps or even days – users are still testing the app, they don’t know everything about it yet, but they are already here. Let’s take Audible – I got my first badge High Noon badge the very second day of listening to my first book. It’s simple.

In both stages my main argument for gamification is fierce competition for attention: let’s just say that it is extremely hard to keep new people on a product.

Users are quick, sceptical and exposed to a lot of alternatives. Even keeping them on a product for 5 more minutes is a huge opportunity and that’s exactly what gamification can do.

Where is gamification rooted?

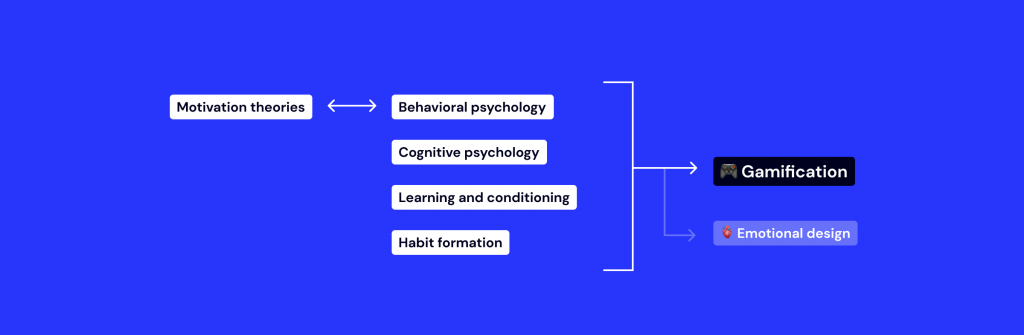

In gamified experiences system goals (e.g. completing steps, engage with content, engage with others) need to be matched with appropriate mechanisms that trigger sentiments, behavior and actions. So in the end of the day, our task is to match the goal with the right gamification tool.

These mechanisms were studied in psychology, neuroscience and were summarised in gaming studies (not to be confused with game theory in economics) : such as rewards, loss avoidance, motivation types, player types and others.

Renown gamification and game models

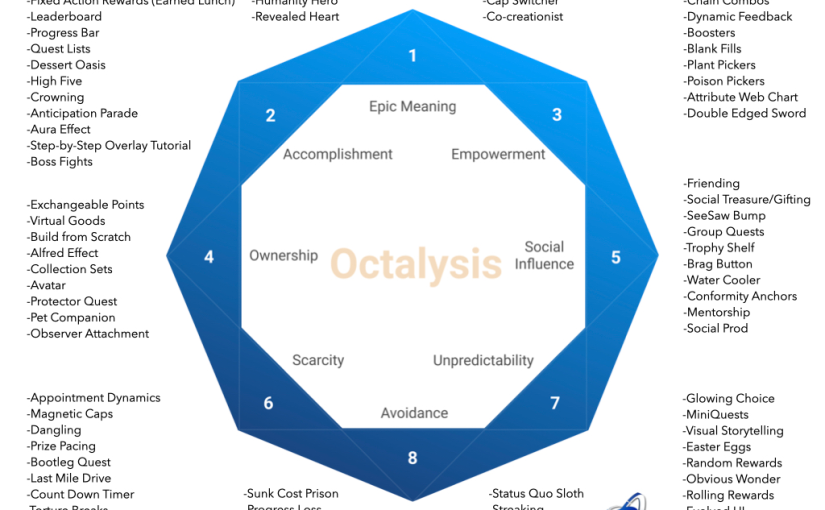

The simplest way to start the journey of gamification is with game design’s best minds. For example, Octalysis framework by Yu-kai Chou defines nearly all aspects of gaming that can easily be transferred into nongame experience. Among other things it describes Accomplishments, Curiosity, Loss and Avoidance as core principles of gaming.

📖 It’s a lot to take in so for a great example of Octalysis in action check this article that examines how Duolingo follows this framework.

Key elements of games

From Users to Players

After getting familiar with principles I suggest to embrace a notion that once we introduce game components users become players. As Yu-kai Chou says, “Different players seek different outcomes and outputs from the game”.

Thinking in terms of players is fundamental: it’s a whole new segmentation we need to introduce to the product, an additional persona trait if you will.

I will mostly refer to Bartles and Marczewski models since Chou’s model is more applicable to games with strong social aspects.

Bartle’s player types are explained well in this Interaction Design Foundation article. There are four player types according to original Bartle’s model: Killers, Achievers, Socializers and Explorers.

Act vs interact, world vs game are dichotomies that Bartle chose for his model. Good news for humanity is that Bartle suggests that only 1% of players are killers, Achievers and Explorers are both 10% and Socialites are 80%.

📖 Other player type models for further references: Andrzej Marczewski player types including non-player users.

Motivation, drivers and rewards

Thinking of variable rewards at this point? They are more to rewards than just variable rewards and it’s a good thing.

Yu-kai Chou, for example, defined 6 types of rewards typical in games and noted that “each user type will need different types of motivation within the system”.

- Fixed action reward: the user knows exactly what they must do to get the reward.

- Random rewards: the participant gets a reward based on completing a required action but they don’t necessarily know what the reward is.

- Sudden rewards: rewards that are not advertised and that the customer doesn’t expect for taking a specific action.

- Rolling rewards (Lottery): are given to a select amount of winners by chance after they take a specific action.

- Social treasure (Gifting): are given by friends, you can’t buy them or earn them.

- Prize pacing: are given in small piece at a time, participants have to collect all the pieces to earn their reward.

These rewards are not mutually exclusive. They are, in fact, combined in games and gamified experiences.

A note on Variable rewards

A hot topic that needs to be addressed is Variable rewards. The concept was popularised by Nir Eyal in Hooked, published in 2013. Being a very thought-provoking book in product and behavioral engineering world, its sole reliance on variable type of rewards can be challenged by gamification design.

Eyals model is a model of habit formation. Eyal was not the only one to conceptualize habit as a loop. In fact, his model relies on Operant conditioning loop of Routine/Behaviour > Reward > Cue.

Another key aspect of the theory is variable ratio and interval reinforcement which was originally studied by Skinner on mice 🐭 in 1938. In mice variable rewards scheduling results in intense compulsive action and reward seeking. Reinforcement theory is one of the most influential theories in psychology and it has been applied in various fields, mainly in behavioral change. Yet Skinner’s comes from behaviorist school, which has been criticised for its sole focus on stimulus-response and disregard of human capacity for reason and emotion.

In today’s behavioral neuroscience, variable rewards and reinforcement theory at large have been studied together with dopamine pathways and reward prediction error (it was also briefly mentioned in Hook’s book). This article by a MD from Cambridge university explains dopamine’s role in motivation and learning in great detail – Dopamine reward prediction error coding, 2016. I would strongly advice getting familiar with this topic from a neuroscience perspective to understand rewards’ role in our behavior and how variable rewards compare to predicted rewards.

Ultimately, There are many takes on rewards, one thing unites them thought. When designing rewards, be aware of reward fatigue! Overuse of extrinsic motivators such as rewards might lead to Overjustification effect: when people become primarily engaged with the reward which subsequently eradicates and replaces the intrinsic motivation they originally had.

I had to witness Overjustification on multiple occasions. One of my favourite example is when both my parents started learning a language on Duolingo and my mother at first posted her leagues advancements in our Whatsapp group. She ultimately announced that it all became about leagues she stopped for a bit. Nevertheless, it did drive her through more than 5 whole chapters, so I guess it is all about short- and long-term goals and stakes.

What about punishment?

There is a notion that rewards are better motivators than punishment. While fear alone is not the most productive motivator, we cannot take this statement for its face value without looking at motivators systems holistically. A simple analysis of games & sports will show us that rewards and a loss of reward (a type of punishment) are very often combined.

Loss aversion is a powerful mechanism and the possibility of losing drives a lot of human behavior. The question is – to which extent can we allow to insinuate a loss in our products? Loss is tricky, it might as well upset people. However, there is always a way to introduce very soft and light weight possibility of “loses” to nudge folks.

Let’s see some examples of combinations or rewards and punishments in Duolingo*

- Reward: higher XP scores are give for a series of right answers

- Punishments: – user loses a heart if the answer is incorrect – less XP is given if users got many answers wrong

*When analysing gamified apps like Duolingo we must be mindful of underlying monetisation strategy. Premium Duolingo account offers unlimited hearts, however, user is still informed that they made a mistake and a “breaking heart” is displayed, it just made made punishment nominal.

Game-like challenges for users

Collections. Games often “challenge” players and offer them well determined goals to pursue. These activities are named with terms similar to “Goal” (e.g. Objectives, Challenges) and often take a shape of a checklist or progress bars. We assume they trigger Achiever type of players.

Foraging. Alongside Goals games use foraging mechanism when a player is aware of a possible reward but isn’t sure of what it is or where exactly they can find it. Sometimes hints to rewards are included in tutorial chapters or via in-game hints. This triggers Explorer type of a player.

Then there is Bargaining – user needs to decide which item to pursue and whether they want to exchange game’s currency, time or effort for a try. It pushes players to be strategic.

Leave a Reply